By Morag Hannah, trainee counsellor specialising in integrative therapies.

Isn’t Counselling a Bit… Self‑Indulgent?

It’s a question people often think but rarely say out loud. And honestly? A counsellor might smile and reply, “I don’t know — is it?”

Because the idea of counselling as “self‑indulgent” usually comes from a deeper belief: that looking after ourselves should be quick, cheap, or squeezed into the margins of life.

But let’s explore that for a moment.

“I Already Have Ways to Cope…”

You might feel you don’t need counselling because:

- you talk to friends

- you go to the gym to burn off stress

- you take a holiday every summer to decompress

- you think things through in your own head

All of these are genuinely valuable. They help you get through life. But they don’t always help you understand why you feel the way you do.

Friends are wonderful, but their loyalty can soften the truth. They want to protect you. They want you to feel better. They want to relate. It’s connection, not clarity.

Exercise can release tension, but it doesn’t explain why the tension built up in the first place. What if the stress you burn off at the gym keeps returning because the root cause hasn’t been explored?

A holiday gives you a break — but what happens when you return home and to the same patterns? Are you content wishing your life away waiting for that annual break rather than enjoying each day with all that it brings, inescapable challenges and joys to savour?

And our minds are brilliant at rationalising, minimising, pushing things aside. Sometimes too brilliant. We can explain away stress, minimise hurt, and convince ourselves that “this is just how life is.”

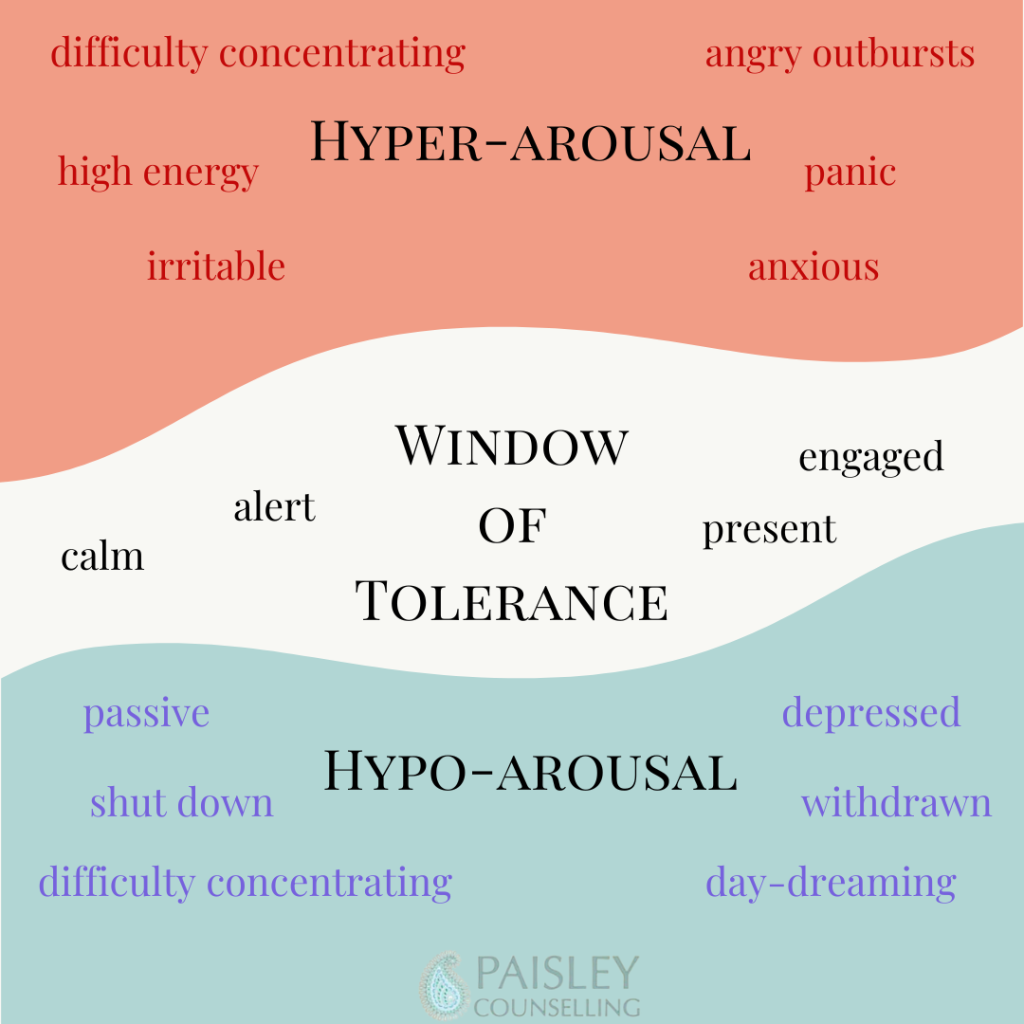

When “Normal” Isn’t Actually Healthy

We all create our own version of normal. We adapt. We cope. We get on with things.

But what if your normal is quietly wearing you down? What if the stress you’ve accepted as “just life” is actually a sign that something needs attention? What if the thoughts you keep to yourself feel too embarrassing or confusing to say out loud and stay unspoken because of fear of judgement?

A counsellor offers something rare: a space where nothing you say is judged, dismissed, or brushed aside. They offer something your own mind can’t: an outside perspective that gently challenges your reality when needed. Not to criticise. Not to shame. But to help you see patterns you’ve been living with for so long that they’ve become invisible.

The Gift of Being Fully Heard

Think about the last time you spoke uninterrupted for more than a minute. No one jumping in with their own story. No one trying to fix you. No one saying, “I know exactly how you feel — that happened to me too.”

My friend and I tease each other about this all the time: “Oh, I have a story like that — but it’s more interesting because I’m in it!”

It’s human nature. We relate by sharing. But counselling is different. It’s one of the few places where the focus stays entirely on you. No competing stories. No need to perform. No pressure to be “fine.” Just space.

There are thoughts you might never say to a friend. Feelings you might not want to burden someone with. Questions about yourself that feel too tender to voice. A counsellor is trained to hear these without flinching. To listen without prejudice. To hold your story without needing you to edit it.

Is It Really Indulgent to Understand Yourself?

We’re legally required to put our cars through a MOT every year. We’re encouraged to service them regularly — because machines need maintenance.

Yet somehow, we expect ourselves to run indefinitely without checking in.

Counselling isn’t indulgent. It’s maintenance for the mind, body and soul. It’s a chance to pause, reflect, and understand the patterns shaping your life with the hope of creating one with even more purpose and meaning.

Counsellors are trained to notice what you say, how you say it, and what sits between the lines. They work at your pace, helping you explore your experiences with curiosity. And sometimes, that gentle exploration is the most responsible, grounded, and compassionate thing you can do for yourself.

Bibliography

- Barlett, S. (2022) ‘Gabor Mate: The Childhood Lie That’s Ruining All Of Our Lives’, The Diary of a CEO with Steven Bartlett [Podcast]. Available at: Spotify Podcasts & Youtube. (Accessed: 7 November 2024).

- Cozolino, L.J. (2016) Why therapy works: Using our minds to change our brains. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Finlay, L. (2025) Relational counselling and psychotherapy. London: Sage.

- Kolk, B.V.D. (2015) The Body Keeps The Score. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

- Rogers, C.R. (1957) ‘The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change.’, Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), pp. 95–103.

- Wallin, D.J. (2007) Attachment in Psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press